Bloom’s Taxonomy: A Comprehensive Overview

Bloom’s Taxonomy: A Comprehensive Overview

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a set of three hierarchical models used to classify educational learning objectives into varying levels of complexity and specificity. This framework helps guide educators in the design of curricula, assessments, and learning objectives across cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains.

Key Takeaways

- Hierarchy: Bloom’s Taxonomy categorizes learning objectives from basic to advanced levels, helping educators scaffold instruction.

- Domains: The taxonomy encompasses cognitive, affective, and psychomotor learning domains.

- Revisions: Initially published in 1956, Bloom’s Taxonomy was revised in 2001 to emphasize active learning processes.

- Criticism: While taxonomy is widely used, it has faced criticisms regarding its hierarchical structure and discrete categorization.

What Is Bloom’s Taxonomy?

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a structured model that categorizes learning objectives into different levels of complexity (Bloom, 1956). The term “taxonomy” may be familiar from biology class, where it refers to the classification of living things from kingdom to species.

Similarly, Bloom’s Taxonomy classifies learning objectives for students, ranging from basic recall of facts to the creation of new and original work.

The model encompasses three domains of learning: cognitive, affective, and psychomotor. Within each domain, learning progresses through various levels, from straightforward to intricate.

Development of the Taxonomy

Benjamin Bloom, an educational psychologist, and the chair of a committee at the University of Chicago, worked with Max Englehart, Edward Furst, Walter Hill, and David Krathwohl in the mid-1950s to create a system that categorized levels of cognitive functioning. This provided a structured approach to understanding different mental processes (Armstrong, 2010).

The team conducted studies on student achievement and identified key factors both within and outside the school environment that influenced how children learn. One notable factor was the limited variation in teaching methods. Teachers often used a one-size-fits-all approach, which failed to address the individual needs of each student.

Bloom and his colleagues proposed that individualized educational plans would significantly improve student learning. This led to the development of Bloom’s Mastery Learning procedure, where teachers organized specific skills and concepts into week-long units.

After completing each unit, students would undergo an assessment to reflect on their learning. The assessments would identify areas needing further support, and students would then be provided with corrective activities to enhance their mastery of the subject (Bloom, 1971).

This approach, guided by Bloom’s Taxonomy, was based on the idea that students could master subjects more effectively when teachers provided appropriate learning conditions and clear learning objectives.

The Original Taxonomy (1956)

The original Bloom’s Taxonomy was introduced in 1956 in the paper “Taxonomy of Educational Objectives” (Bloom, 1956). It presents a hierarchy of learning objectives organized by complexity, suggesting that students should progress through these levels sequentially. Students must demonstrate mastery of one level through formative assessments, remedial activities, and enrichment exercises before advancing to the next level (Guskey, 2005).

Three Domains of Learning.

- Cognitive (thinking)

- Affective (feeling)

- Psychomotor (doing)

1. Cognitive Domain: Concerned with thinking and intellect.

Bloom’s Taxonomy, originally created by Benjamin Bloom in 1956, is a hierarchical model of cognitive processes that categorizes learning objectives from simple to complex. It consists of six levels, each representing a different stage of learning and thinking. The levels are designed to help educators develop comprehensive learning goals and assessments.

- Knowledge: This is the lowest level, where learners recall or recognize facts, terms, basic concepts, or answers without necessarily understanding them.

- Example: List the major events of World War II.

- Comprehension: At this level, learners demonstrate their understanding of information by interpreting or explaining it.

- Example: Summarize the causes and effects of World War II.

- Application: This level involves using learned knowledge in new but similar situations.

- Example: Apply the lessons learned from World War II to a hypothetical modern conflict.

- Analysis: At this level, learners break down information into its components and explore relationships between them.

- Example: Compare and contrast the strategies used by the Allied and Axis powers during World War II.

- Synthesis: Learners combine elements to form a new structure or create something original.

- Example: Create a plan for a commemorative event honoring World War II veterans.

- Evaluation: This is the highest level, where learners make judgments based on criteria and standards, and critique information.

- Example: Evaluate the impact of World War II on contemporary global politics.

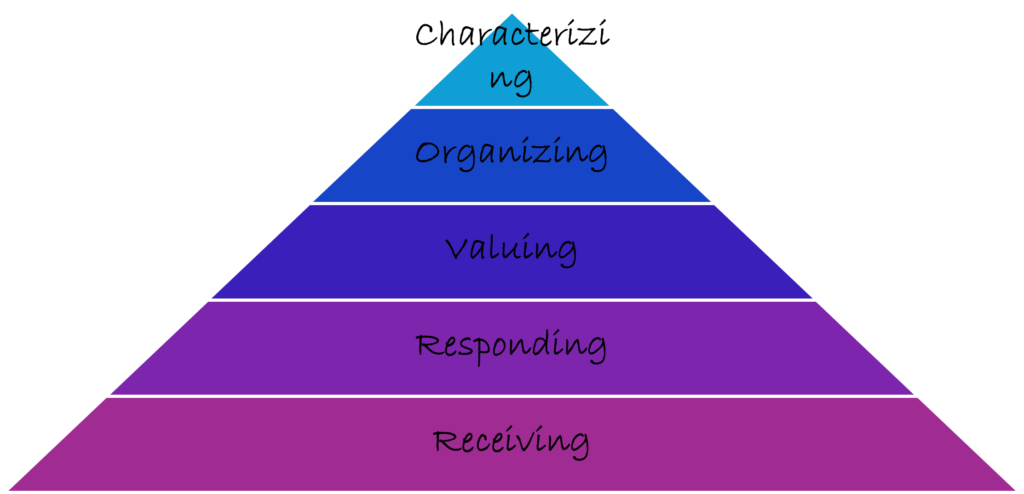

2. Affective Domain: Focuses on emotions, attitudes, values, and motivations.

The affective domain focuses on emotions, attitudes, values, and motivations. It includes five levels:

- Receiving: Being open to new experiences. For example, listening to a lecture and being open to new ideas.

- Responding: Actively engaging with information. For example, participating in a class discussion or group activity.

- Valuing: Assigning worth to knowledge or experiences. For example, appreciating cultural diversity or recognizing the importance of a healthy lifestyle.

- Organizing: Integrating values into a coherent system. For example, prioritizing ethical standards in decision-making.

- Characterizing: Internalizing values to guide behavior consistently. For example, demonstrating empathy and respect for others in daily interactions.

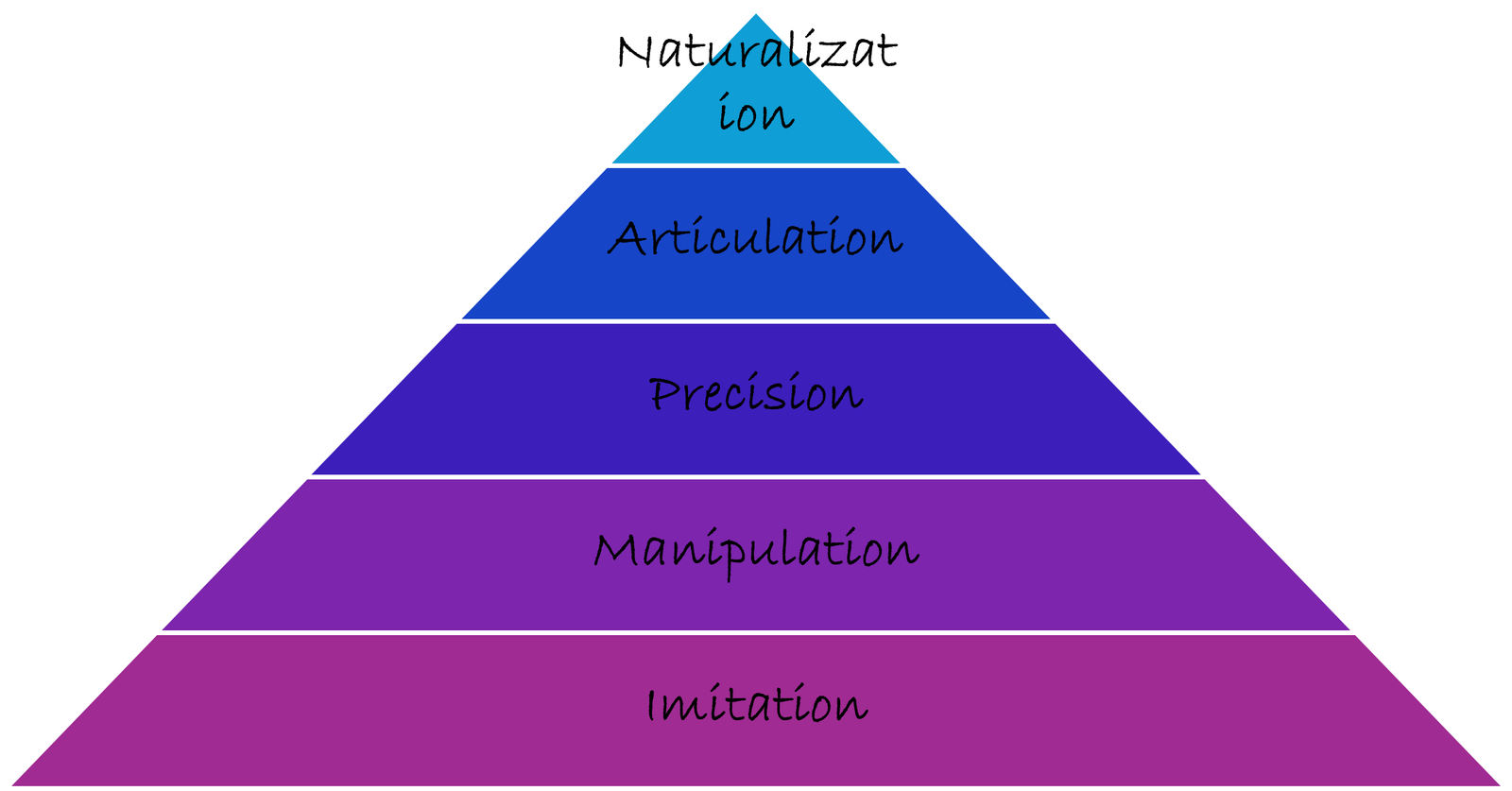

3. The Psychomotor Domain (1972): Understanding Skilled Behavior

The psychomotor domain in Bloom’s Taxonomy involves the ability to physically handle tools and equipment with precision. It includes physical movement, coordination, and the use of motor skills. The focus is on skill development and mastering physical and manual tasks.

Mastery in this domain is marked by speed, accuracy, and consistency. Psychomotor skills range from simple activities like washing a car to complex tasks such as operating advanced technological equipment.

Over time, the psychomotor domain has evolved. Robert Armstrong and his colleagues in 1970 were among the first to develop a taxonomy for the psychomotor domain of Bloom’s Taxonomy. This domain focuses on the development and mastery of physical and manual skills through movement, coordination, and manipulation. Armstrong’s taxonomy outlined five levels of psychomotor development, each representing different degrees of performing a skill, from initial exposure to mastery:

- Imitation: The initial stage of psychomotor learning involves observing and imitating a demonstrated action. For example, a student watches a teacher’s demonstration of how to correctly write on a whiteboard.

- Manipulation: At this stage, the learner practices the skill through repetition and trial and error, gradually gaining confidence and proficiency. For example, a student repeatedly practices writing letters on the board to improve their handwriting.

- Precision: As the learner becomes more skilled, they focus on performing the task with accuracy and precision. For instance, a student aims to write letters of consistent size and shape on the board.

- Articulation: In this level, the learner integrates multiple skills into complex and coordinated movements. For example, a student combines writing with drawing to create a well-organized visual presentation.

- Naturalization: The highest level involves the learner performing the skill automatically and naturally without conscious effort. For example, a student effortlessly writes and draws on the board while explaining a concept to the class.

Armstrong’s taxonomy provides a framework for educators to understand the progression of psychomotor learning and to design instructional strategies that support students in mastering physical skills.

Anita Harrow (1972)

In 1972, Anita Harrow proposed a revised taxonomy for the psychomotor domain, building upon the earlier work of Robert Armstrong and his colleagues. Harrow’s model introduced six levels of psychomotor development, focusing on the progression of physical skills from basic reflexes to advanced, expressive movements:

- Reflex Movements: The most basic level involves automatic, involuntary movements in response to a stimulus, such as blinking when an object approaches the eyes.

- Fundamental Movements: At this stage, the learner develops basic motor skills, such as walking, running, jumping, and other foundational movements necessary for more complex activities.

- Perceptual Abilities: This level involves using the senses to guide physical movements, such as coordinating hand-eye movements to catch a ball.

- Physical Abilities: The learner develops physical fitness, including strength, flexibility, and endurance, which supports the performance of skilled movements.

- Skilled Movements: At this level, the learner achieves proficiency in specific tasks or techniques, such as playing a musical instrument or painting a picture.

- Non-discursive Communication: The highest level involves expressing oneself through physical movements without the use of words, such as through dance or body language.

Harrow’s taxonomy provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the stages of psychomotor development and highlights the importance of sensory perception and physical fitness in mastering skilled behaviors. This model is valuable for educators designing curricula that involve physical activities and the development of motor skills.

Elizabeth Simpson (1972)

In 1972, Elizabeth Simpson developed a taxonomy of the psychomotor domain that outlines the progression of physical and motor skills from observation to the invention of new movements. Simpson’s taxonomy includes seven levels, each describing different stages of psychomotor learning and development:

- Perception: The first level involves using sensory cues to guide physical movements. For example, estimating where a ball will land and positioning oneself to catch it.

- Set: This level involves readiness to act, both physically and mentally. For instance, a student preparing to throw a perfect strike in baseball recognizes their current skill level and expresses the desire to improve.

- Guided Response: At this stage, the learner begins to master physical skills through practice and guidance. This involves trial and error, such as throwing a ball under the guidance of a coach and focusing on specific movements.

- Mechanism: This level represents intermediate skill mastery, where learned responses become habitual and can be performed with confidence and proficiency. For example, successfully throwing a ball to the catcher consistently.

- Complex Overt Response: At this stage, the learner can skillfully perform complex movements automatically and without hesitation. For instance, consistently throwing perfect strikes in baseball.

- Adaptation: This level involves modifying skills based on specific requirements and adapting to different situations. For example, adjusting a throw to accommodate a batter at the plate.

- Origination: The highest level, origination, involves creating new movements or combining existing skills to address novel situations. For instance, using the skills needed to throw a fastball to learn how to throw a curveball.

Simpson’s taxonomy provides a detailed framework for understanding the development of motor skills, starting from perception and progressing to the ability to innovate and create new movements. This model is valuable for educators and trainers aiming to support learners in mastering physical and motor tasks.

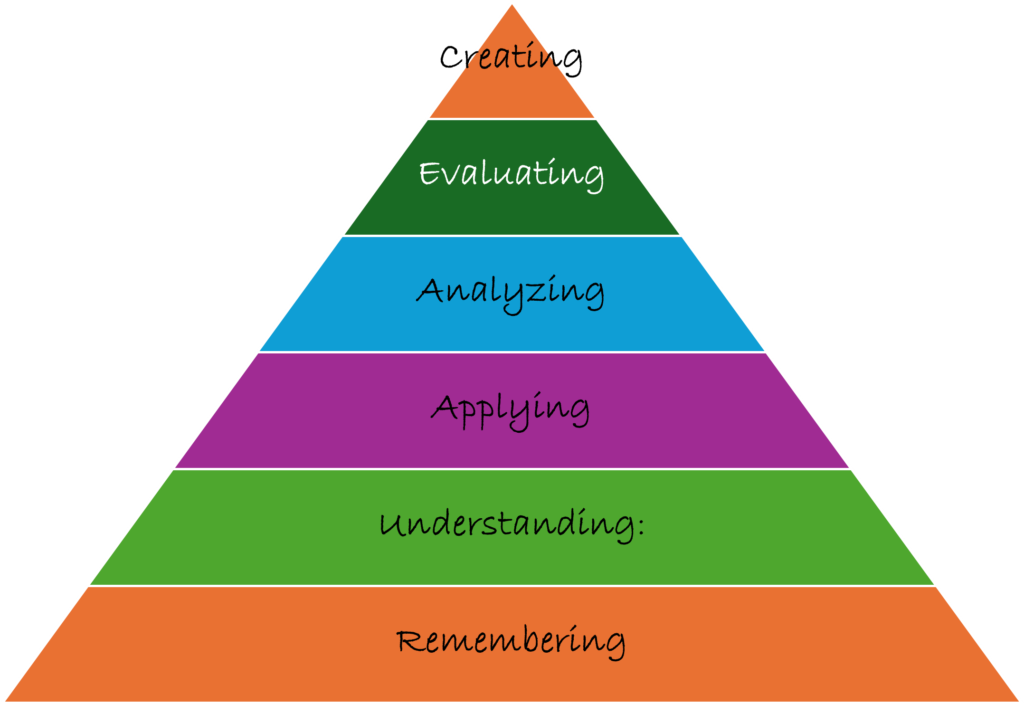

Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy

In 2001, a group of cognitive psychologists, led by Lorin Anderson and David Krathwohl, revised Bloom’s Taxonomy to reflect a more contemporary understanding of educational practices and learning processes. The revised taxonomy restructured the original six categories of the cognitive domain, with a few significant changes:

- Remembering: Recalling facts and basic concepts. For example, remembering historical dates and events or mathematical formulas.

- Understanding: Explaining ideas and concepts. For example, interpreting a story’s moral or explaining the steps of a scientific experiment.

- Applying: Using knowledge in new situations. For example, applying learned mathematical formulas to solve word problems.

- Analyzing: Breaking down information to explore relationships. For example, analyzing a novel’s characters and plot to understand themes.

- Evaluating: Making judgments based on criteria and standards. For example, evaluating the effectiveness of different methods in an experiment.

- Creating: Generating new ideas or combining existing ones. For example, creating an original story or designing an experiment to test a hypothesis.

The revised Bloom’s Taxonomy also emphasizes the hierarchical nature of these cognitive processes, but with a more dynamic structure. In this version, the taxonomy is often presented as a wheel or a set of interconnected skills, acknowledging that learning is an ongoing process that may involve moving back and forth between different levels.

Overall, the 2001 revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy helps to better reflect the complexity of cognitive tasks and the interrelationships between different levels of thinking, offering a more flexible and nuanced approach to understanding and assessing learning outcomes.

Critical Evaluation

Bloom’s Taxonomy effectively structures the complex concept of thinking into a tangible and organized framework.

Educators continue to rely on the taxonomy to guide the way they set learning objectives and design their curriculum.

By using questions or assignments that align with Bloom’s principles, students are encouraged to engage in higher-level thinking.

Despite its ongoing use, the taxonomy is not without its shortcomings. The original 1956 taxonomy presented learning as a fixed concept, which the 2001 revised version addressed by using active verbs to highlight the dynamic nature of learning. However, the updated structure still faces multiple critiques.

One common criticism is the hierarchical nature of the taxonomy, which implies that cognitive steps are distinct and must be undertaken independently (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). In practice, many tasks require multiple cognitive skills working together simultaneously rather than sequentially.

The pyramid structure also suggests that some cognitive skills are more challenging and important than others, potentially devaluing the importance of knowledge and comprehension. However, these foundational skills are just as crucial as the higher-order processes at the top of the pyramid.

This hierarchy contributes to a trend of downplaying the significance of knowledge, which can negatively impact lower-income students who may have less access to sources of information and face a knowledge gap in schools.

Another issue is that the linear sequence of cognitive steps may not accurately reflect how learning occurs. Often, learning begins with applying and creating rather than solely remembering and comprehending. For instance, one learns to write an essay by actually writing one or to speak Spanish by practicing the language.

Learning happens through active engagement in tasks rather than following a strict, linear path. Despite these criticisms, Bloom’s Taxonomy remains a widely used model in education today.